GLP-1 Drugs Have Emerged as a Panacea for Addiction – If You Can Afford Them

This is the second of our three-part series on The Ozempic Era. This series explores how the Food Industrial Complex engineered an addiction crisis, how Ozempic emerged as its apparent antidote, and why millions of desperate patients betting their health on GLP-1 drugs may be making a deal with the devil.

Read The Ozempic Era, Part 0: Preview

Read The Ozempic Era, Part I: Craveware.

The Rise of Ozempic: Medicine’s New “Silver Bullet“

The story of how GLP-1 agonists transformed from diabetes medication to potential addiction panacea begins, like many medical breakthroughs, with an unexpected observation and a Eureka moment.

Eureka! Discovering the Miracle Drug

Ozempic’s story begins in the labs of researchers seeking to better manage type 2 diabetes. Clinicians began to notice that diabetes patients taking semaglutide – a peptide drug sold by Novo Nordisk under the brand name Ozempic – weren’t just achieving better blood sugar control 1. They were shedding significant amounts of weight. Not the modest few pounds traditionally seen with other diabetes medications, but dramatic losses of 15% or more of their total body weight 2.

What made this weight loss different was its consistency. Previous weight loss medications had modestly helped some patients dramatically while doing virtually nothing for others. But semaglutide delivered significant results across broad populations.

More importantly, patients described a profound shift in their relationship with food. The constant cravings, the intrusive thoughts about eating, the loss of control around certain hyperpalatable foods – these hallmarks of food addiction began to fade. For the first time, physicians had a tool that seemed powerful enough to counter the biochemical trickery of engineered “craveware” foods.

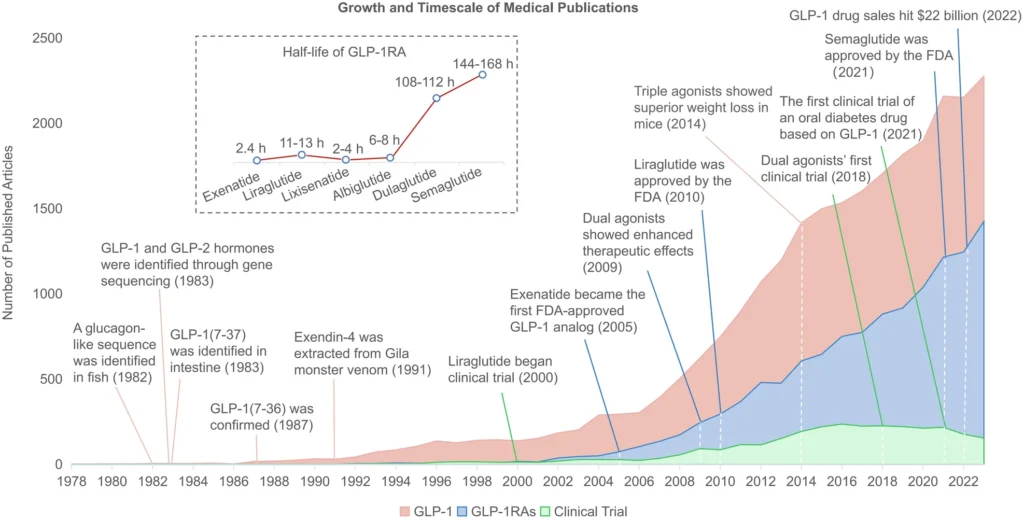

Figure: GLP-1 research and commercial milestones, 1978-2022 3

A Solution to Addictive “Craveware”

At Ozempic’s core is semaglutide, a synthetic version of a naturally occurring hormone called GLP-1 (glucagon-like peptide-1) that is typically administered once a week via a subcutaneous injection. The body naturally releases GLP-1 after meals to regulate and protect the body. Semaglutide supercharges that process: by binding to GLP-1 receptors in the pancreas, brain, and stomach, semaglutide slows gastric emptying, reduces appetite through direct action on brain centers, improves insulin sensitivity, and – most intriguingly – appears to modulate the very reward circuits that make hyperpalatable foods so irresistible 4.

Yet the drug’s wide-ranging impact doesn’t stop at waistlines. As more data emerged, researchers began noticing something even more remarkable: GLP-1 drugs appear to slow neurodegenerative diseases 5 and curb addiction-related behaviors beyond just food 6. Early studies suggested potential benefits for alcohol cravings, nicotine dependence, and other compulsive behaviors. The implications were profound: had we stumbled upon a master key to human cravings?

The Weight Loss Drug Gold Rush

Once word got out that a “miracle shot” could slash body weight by double digits, demand exploded. By early 2024, approximately one in eight American adults reported having taken a GLP-1 agonist 7. Novo Nordisk, the Danish pharmaceutical giant behind Ozempic and Wegovy, saw a massive revenue surge and became Europe’s most valuable company 8. Competitors hustled to keep pace.

The FDA’s GLP-1 agonist approval timeline reveals the frenzied pace of the weight loss medication gold rush:

| Year Approved | Brand Name | Drug Component | Company | Approved Use |

| 2005 | Byetta | Exenatide | AstraZeneca | Type 2 diabetes |

| 2010 | Victoza | Liraglutide | Novo Nordisk | Type 2 diabetes |

| 2014 | Saxenda | Liraglutide | Novo Nordisk | Chronic weight management |

| 2017 | Ozempic | Semaglutide | Novo Nordisk | Type 2 diabetes |

| 2019 | Rybelsus | Semaglutide | Novo Nordisk | Type 2 diabetes |

| 2021 | Wegovy | Semaglutide | Novo Nordisk | Chronic weight management |

| 2022 | Mounjaro | Tirzepatide | Eli Lilly | Type 2 diabetes |

| 2023 | Zepbound | Tirzepatide | Eli Lilly | Chronic weight management |

Eli Lilly wasn’t far behind. Eli Lilly’s tirzepatide (Mounjaro/Zepbound) added a second mechanism of action, targeting both GLP-1 and GIP (gastric inhibitory polypeptide) receptors 9. The weight loss results approached bariatric surgery territory – up to 20% total body weight loss in clinical trials 10 – but without permanent anatomical alterations.

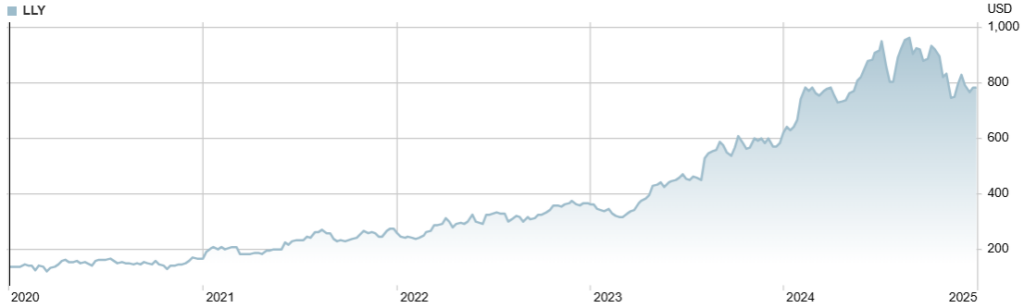

While tirzepatide patients have been slimming down, Eli Lilly has been fattening up: Eli Lilly’s valuation has tripled to nearly $1 trillion 11, eclipsing Novo Nordisk’s early dominance and catapulting it to the top of list of world’s most valuable healthcare companies 12.

Figure: Eli Lilly stock price, 2020-2024 13

The broader pharmaceutical industry has taken notice. Tirzepatide and semaglutide are currently considered the most effective medications for weight loss 14, but at least 16 new obesity drugs are anticipated to enter the market in the next five years 15. Companies including Roche, Amgen, Pfizer, and AstraZeneca are all racing to claim their share of what promises to be a $100+ billion market.

Is Ozempic Too Good to Be True?

The medical community’s excitement is understandable. For decades, we’d fought the obesity epidemic with tools that seemed hopelessly mismatched against the sophisticated engineering of modern processed foods. Now, at long last, we have a pharmaceutical intervention that can potentially disrupt the very reward pathways that make industrially engineered foods so addictive.

Ozempic’s Physical Toll

The first signs of trouble appeared in the routine follow-up visits. Patients reported dramatic weight loss success, yes, but something else was happening to their bodies. Physicians began noticing troubling gastrointestinal symptoms and changes in body composition.

The gastrointestinal side effects have been well documented: nausea, vomiting, and constipation so severe that they rank among the top reasons for patient discontinuing GLP-1 medications 16. And yet, these immediate discomforts may prove less significant than the longer-term changes happening beneath the surface.

Recent research has revealed that up to one-third of the weight lost on GLP-1 medications comes from lean muscle mass rather than fat 17. This isn’t just a cosmetic concern. The gradual loss of muscle mass and strength can lead to a cascade of negative health outcomes: lower metabolic rates, reduced functional capacity, and an increased risk of developing what researchers call “skinny fat” syndrome – normal weight but metabolically unhealthy 18.

“My biggest concern with GLP-1s is that they may be too effective,” one obesity medicine specialist with nearly two decades of primary care experience shared with me. “These drugs can completely eliminate appropriate hunger, which is a normal and necessary human phenomenon. If patients are happy without eating, that’s dangerous – they lose lean mass.” Some physicians are now finding that in certain cases, it may be better for patients to remain overweight but preserve muscle mass than to achieve dramatic weight loss at the expense of lean tissue.

Some patients have also reported dramatic changes in facial aging, dubbed “Ozempic face” in the media 19. While this might seem superficial compared to the aforementioned medical concerns, unwanted changes in face composition can take a major psychological toll. More concerningly, these surface-level changes hint at a broader pattern of rapid physiological changes caused by Ozempic that have profound consequences for health and aging. More on this in Part III.

Ozempic Helps Weight Loss, but It’s Not an Obesity Cure

The drugs work. The weight comes off. Patients report reduced cravings and improved control over their appetites. “These medications create mental headspace,” one obesity medicine specialist with nearly two decades of clinical experience explained to me. “When you’re not constantly battling cravings, when your brain isn’t overwhelmed with intrusive thoughts about food, you finally have the capacity to do the hard work of changing your relationship with eating.”

Hard work is the opposite of a silver bullet. This window of opportunity – this period of reduced cravings and increased control – represents a crucial chance for patients to establish new habits and behaviors. But here’s the critical caveat: GLP-1 drugs aren’t an obesity cure. They only control cravings and addictions while actively taking them. Unless patients use this window to fundamentally change their lifestyle and relationship with food, the cravings will return with a vengeance as soon as they stop the medication.

This caveat transforms GLP-1 drugs from a miracle cure to a maintenance medication. In the worst-case scenario, they’re a life sentence. Like insulin for diabetes or antidepressants for depression, they become part of a long-term strategy for managing chronic disease. “We need to shift our understanding of obesity,” argues another obesity medicine specialist. “This isn’t about willpower or short-term fixes. It’s a chronic disease that requires ongoing treatment, just like hypertension or diabetes.”

But this is where the promise of GLP-1 drugs collides with the harsh realities of American healthcare. The support infrastructure needed to help patients make lasting changes – the behavioral health resources, the nutritional counseling, the coordinated care teams – is largely missing.

The Health System Isn’t Ready for Weight Loss Patients

Beyond the physical side effects, our healthcare system is fundamentally unprepared to manage patients on these medications. The data is clear: GLP-1 patients have the greatest success with high-touch, coordinated care that combines medication management with lifestyle interventions 20. Yet our primary care infrastructure isn’t built to deliver this level of support.

Primary care physicians (PCPs) are poorly equipped for the kind of high-touch health management required to successfully navigate the weight loss journey 21:

- Low bandwidth: Primary care providers often lack the bandwidth to offer the intense patient engagement and support needed for healthy, lasting weight loss. Initiating, titrating, and monitoring GLP-1 drugs significantly adds to PCP workloads. And it takes a lot of time and effort to help patients navigate the drug’s side effects and required lifestyle modifications.

- Inexperienced: Medical professionals often lack experience in obesity management. Primary care providers aren’t necessarily fully aware of the comprehensive care required, from addressing nutritional biochemistry to understanding mitochondrial dysfunction.

- Poorly resourced: Many PCPs lack the resources necessary for proper patient screening and monitoring. PCPs and clinics also often don’t have access to the multidisciplinary care teams – diabetes care specialists, bariatric health care providers, dietitians, nutritionists – needed for comprehensive obesity management. They are also unable to provide adequate coaching on nutrition and exercise practices to improve weight loss outcomes while on the drug.

The result? Many patients receive prescriptions without the comprehensive support system needed for long-term success 22. They’re left to navigate severe side effects, complex lifestyle changes, and critical nutritional needs largely on their own. Often this leads to a failure to modify consumption behaviors, discontinuation of treatment, and rapid weight regain.

The Dark Side of Ozempic: Treatment Roulette

The stark reality of GLP-1 drugs emerges in a single devastating statistic: only 15% of U.S. patients prescribed GLP-1 drugs for weight loss continue treatment after two years 23. This bleak adherence figure should horrify anyone concerned with public health and solving the obesity crisis.

These drugs aren’t just another diet pill – they represent our best tool yet for treating food addiction. But this treatment only works with sustained access and support. Those conditions are proving to be a very tall order for the American healthcare system.

Weight Loss Drugs’ Pervasive Supply Shortages

Ozempic’s success brought its own complications. From day one, Wegovy and Zepbound – Novo’s and Lilly’s respective weight loss medications – have been in critically short supply. Manufacturing has consistently struggled to keep pace with skyrocketing demand, creating a chaotic landscape where diabetes patients find themselves competing with weight loss seekers for limited supplies of Ozempic and Monjouro, which are intended for diabetes management 24.

Healthcare providers have spent multiple years grappling with unreliable availability, forcing healthcare providers into impossible choices about patient prioritization. “Semaglutide and tirzepatide supply issues were a significant problem [in 2024],” emphasizes Dr. Laura Davisson, Professor of Medicine and Director of Medical Weight Management at West Virginia University. “Not every patient who needs to lose weight needs a GLP-1, but obesity medicine specialists should be able to make [treatment] decisions based on medical reasons.”

Weight Loss Drugs’ Onerous Financial Burden

Supply is only half the problem. The other half is price. The cost burden of Ozempic on patients is staggering. With a price tag of over $12,000 per year, most patients face difficult choices about starting or continuing treatment.

Despite the drugs’ significant weight-loss efficacy, the ongoing financial burden makes GLP-1 drugs inaccessible for many – particularly for uninsured or underinsured populations. A recent study found that 54% of people on GLP-1 drugs reported difficulty managing the cost, including 22% who described it as “very difficult.” Even among insured users, 53% struggled with affordability 25.

A comprehensive analysis revealed that individuals without diabetes who began GLP-1 drugs for obesity saw their healthcare costs increase by $4,206 in their second year compared to those not on GLP-1 therapy. Contrary to popular expectation, weight loss drugs did not lead to a reduction in obesity-related medical episode (e.g. diabetes, cardiovascular disease) costs 26.

This dramatic increase in net cost of care – the costs of GLP-1 therapy minus savings due to reduced obesity-related medical issues – for obesity treatment raises serious questions about the long-term cost-effectiveness of these treatments for both individual patients and the healthcare system as a whole.

Health Insurers Beat a Hasty Retreat

Most employer plans limit or exclude coverage of weight loss medications, leaving many to pay out-of-pocket 27. “Access is currently being decided based on whether these medications are included in someone’s plan,” Dr. Davisson continues. “[Even] if the medications are on someone’s plan, extremely variable sets of restrictions are being placed on access. The hoops a patient has to jump through are inconsistent between every different plan.”

In response to supply and cost pressures, several major insurance companies are dropping the pretense and are entirely eliminating coverage of these medications for obesity 28. ACA Marketplace plans limit GLP-1 drug coverage to patients with chronic diseases like diabetes 29. Medicare prohibits coverage of anti-obesity medications unless used to treat other conditions, such as type 2 diabetes or cardiovascular disease.

Such carveouts would be unthinkable for almost any other chronic disease. But the message is clear: obesity treatment remains categorized as cosmetic or lifestyle-related rather than medically necessary, despite overwhelming evidence to the contrary. These coverage exclusions ignore the chronic disease nature of obesity and ignore the complex relationship between obesity and metabolic conditions such as diabetes.

Treatment Roulette

These supply shortages and insurance coverage restrictions are increasingly placing the brunt of the psychological and financial burden on medically uneducated, socioeconomically disadvantaged portions of the population. For patients, this often results in playing a dangerous game of treatment roulette – never knowing if their next prescription will be filled.

These treatment interruptions aren’t just inconvenient; they undo months of weight loss progress and jeopardize patients’ health. When treatment stops abruptly, patients often experience rapid weight regain along with the return of the food cravings and behavioral patterns they had worked so hard to overcome.

Temporary Relief: The Era of Cheap Compounded GLP-1s

As millions of Americans face the harsh realities of drug access barriers, a shadow healthcare system has emerged to fill the gap. Millions of patients, priced out of Ozempic and desperate to maintain their weight loss progress, turned to compounding pharmacies that offer generic versions of weight loss medications at a fraction of the cost. Compounding pharmacies, once a niche player in pharmaceutical manufacturing, have become an essential lifeline for patients desperate to maintain their weight loss treatment.

GLP-1 Compounders Fill the Gap

The appeal of compounded GLP-1 drugs is immediately obvious: while branded GLP-1s cost upwards of $1,300 monthly, compounded versions typically run $300-400. For the majority of patients struggling with insurance denials or prohibitive copays, this price difference is the difference between continuing treatment and being forced to stop.

But cost savings are only part of the story. When supply chain chaos left pharmacy shelves empty of brand-name Ozempic, Wegovy, Mounjaro, and Zepbound, compounding pharmacies kept patients on therapy who would otherwise have faced dangerous treatment interruptions 30.

Under FDA emergency rules, official compounding facilities can legally gain authorization to produce medications during officially declared shortages. The FDA declared a semaglutide shortage in March 2022 and tirzepatide shortage in December 2022 31.

The process of drug compounding appears at first glance relatively straightforward: pharmacists combine pharmaceutical ingredients to create versions of semaglutide or tirzepatide that mirror the active components of branded drugs. While not identical to the originals, these compounded versions offered a viable alternative for many patients.

The numbers tell the story: an estimated 30% of GLP-1 users in the United States have obtained their medication from compounding pharmacies 32. That’s potentially millions of Americans who found a path to continued treatment through this alternative channel.

Pharma Giants Raise the Alarm

The pharmaceutical giants didn’t welcome the competition. Novo Nordisk and Eli Lilly launched aggressive campaigns questioning the safety and consistency of compounded medications. Their argument centered on quality control: because compounded drugs don’t undergo the FDA’s standard review process, they claimed, variations in purity, potency, or sterility could put patients at risk 33.

Many obesity advocacy organizations and specialists have aligned with this position, refusing to work with compounded versions entirely. “Patient safety comes first,” explains Dr. Maribeth Orr, a board-certified Obesity Medicine physician at Heartland Weight Loss. “While we want nothing more than for patients to get treatment, we can’t support something so unregulated and risky.”

Compounding pharmacies and their supporters argue that these concerns are overblown, pointing to their long history of safely producing numerous other medications and their adherence to strict quality control standards. They see a different motivation behind Big Pharma’s opposition 34: with GLP-1 medications projected to become a $100+ billion market, pharmaceutical companies have an obvious interest in maintaining their oligopoly and pricing power. The existence of much cheaper compounded alternatives threatens their profit potential 35.

The pharmaceutical companies haven’t limited their response to public relations. They’ve backed their safety concerns with legal muscle, filing lawsuits and lobbying intensively to restrict compounding. Eli Lilly, in particular, has taken an aggressive stance against sellers of compounded tirzepatide versions 36.

The safety of legal compounded medications remains contested. While official compounding pharmacies are required by the FDA to follow strict protocols, they indeed don’t face the same rigorous oversight as large pharmaceutical manufacturers. Furthermore, the FDA has received numerous safety complaints about certain compounded GLP-1 formulations, underscoring this risk 37. And beyond legal compounders, dark market GLP-1 drug sellers operate with no regulatory oversight, posing severe health and legal risks for consumers 38.

However, for many patients desperately seeking treatment, the choice isn’t between branded and compounded medications – it’s between compounded medications and no treatment at all 39. When framed in these terms, the decision for many is simple.

The Rug Pull: FDA Declares the Shortage Over

For a moment, it seemed that off-label use and compounding might offer a supply and cost solution for patients, helping to maintain drug access. Patients facing treatment disruption due to supply shortages had an alternative source. The existence of this parallel market even creates some pressure on pharmaceutical companies to reconsider their pricing strategies 40.

But now some patients’ window of hope is rapidly closing. The FDA has declared the tirzepatide shortage over, and semaglutide will quickly follow suit, portending doom for the GLP-1 compounding market 41. This declaration leaves vulnerable patients with an impossible choice: pay thousands for name brand medications or stop treatment altogether. Millions more patients may join the 85% of people who discontinue weight loss treatment within two years.

The consequences of this mass discontinuation may prove catastrophic. As we’ll explore in Part III, there’s growing evidence that prematurely disrupting GLP-1 treatment can have severe negative physiological consequences.

When the dust settles, America’s experiment with GLP-1 drugs may prove to have been a deal with the devil: attracting millions with the unprecedented hope of curing food addiction and obesity, only to leave patients worse off – financially, physically, and psychologically – than ever before.

- Zheng, Zhikai, et al. “Glucagon-like peptide-1 receptor: Mechanisms and advances in therapy.” Signal Transduction and Targeted Therapy, vol. 9, no. 1, 18 Sept. 2024. ↩︎

- “Chronic Weight Management.” novoMEDLINK. ↩︎

- Zheng, Zhikai, et al. “Glucagon-like peptide-1 receptor: Mechanisms and advances in therapy.” Signal Transduction and Targeted Therapy, vol. 9, no. 1, 18 Sept. 2024. ↩︎

- “Ozempic for Weight Loss: Who Should Try It and Will It Work?” Cleveland Clinic, 10 July 2024. ↩︎

- Zheng, Zhikai, et al. “Glucagon-like peptide-1 receptor: Mechanisms and advances in therapy.” Signal Transduction and Targeted Therapy, vol. 9, no. 1, 18 Sept. 2024. ↩︎

- Zheng, Zhikai, et al. “Glucagon-like peptide-1 receptor: Mechanisms and advances in therapy.” Signal Transduction and Targeted Therapy, vol. 9, no. 1, 18 Sept. 2024. ↩︎

- Montero, Alex, et al. “KFF Health Tracking Poll May 2024: The Public’s Use and Views of GLP-1 Drugs.” KFF, 10 May 2024. ↩︎

- “Largest Companies in the EU by Market Capitalization.” CompaniesMarketcap. ↩︎

- Rodriguez, Patricia J., et al. “Semaglutide vs tirzepatide for weight loss in adults with overweight or obesity.” JAMA Internal Medicine, vol. 184, no. 9, 8 July 2024, pp. 1056–1064. ↩︎

- Aronne, Louis. “Tirzepatide Enhances Weight Loss with Sustained Treatment but Discontinuation Leads to Weight Regain.” Weill Cornell Medicine, 11 Dec. 2023. ↩︎

- Constantino, Annika Kim, and Ashley Capoot. “Healthy Returns: Eli Lilly Could Soon Become the First $1 Trillion Health-Care Stock.” CNBC, 5 Sept. 2024. ↩︎

- “Largest pharma companies by market cap.” CompaniesMarketcap. ↩︎

- “Stock Quote & Chart.” Eli Lilly. ↩︎

- Castro, M Regina. “Do Any Diabetes Medicines Help You Lose Weight?” Mayo Clinic, 14 Nov. 2024. ↩︎

- “Obesity Drug Market: The next Wave of GLP-1 Competition.” Morningstar, Inc. ↩︎

- Sikirica, Mirko, et al. “Reasons for discontinuation of GLP1 receptor agonists: Data from a real-world cross-sectional survey of physicians and their patients with type 2 diabetes.” Diabetes, Metabolic Syndrome and Obesity: Targets and Therapy, Volume 10, Sept. 2017, pp. 403–412. ↩︎

- Prado, Carla M, et al. “Muscle matters: The effects of medically induced weight loss on skeletal muscle.” The Lancet Diabetes & Endocrinology, vol. 12, no. 11, Nov. 2024, pp. 785–787. ↩︎

- Prado, Carla M, et al. “Muscle matters: The effects of medically induced weight loss on skeletal muscle.” The Lancet Diabetes & Endocrinology, vol. 12, no. 11, Nov. 2024, pp. 785–787. ↩︎

- Donnelly, Brian. “Ozempic Face: The Cosmetic Concerns of Rapid Weight Loss.” Northwell Health, 26 Nov. 2024. ↩︎

- White, Gretchen E, et al. “Real-World Weight-Loss Effectiveness of Glucagon-like Peptide-1 Agonists among Patients with Type 2 Diabetes: A Retrospective Cohort Study.” Obesity (Silver Spring, Md.), 9 Jan. 2023. ↩︎

- Terhune, Chad. “Exclusive: Most Patients Stop Using Wegovy, Ozempic for Weight Loss within Two Years.” Reuters, 10 July 2024. ↩︎

- Terhune, Chad. “Exclusive: Most Patients Stop Using Wegovy, Ozempic for Weight Loss within Two Years.” Reuters, 10 July 2024. ↩︎

- Gleason, Patrick, et al. “Year-Two Real-World Analysis of Glucagon-Like Peptide-1 Agonist (GLP-1) Obesity Treatment Adherence and Persistency.” Prime Therapeutics / Magellan Rx Management, July 2024. ↩︎

- Sheppard, Sarah. “Shortages Impacting Access to Glucagon-like Peptide 1 Receptor Agonist Products; Increasing the Potential for Falsified Versions.” World Health Organization, 29 Jan. 2024. ↩︎

- Montero, Alex, et al. “KFF Health Tracking Poll May 2024: The Public’s Use and Views of GLP-1 Drugs.” KFF, 10 May 2024. ↩︎

- “Prime Therapeutics GLP-1 Research: Year-2 Cost of Care Is $4,200 Higher for Patients with Obesity.” Prime Therapeutics, 24 Oct. 2024. ↩︎

- Montero, Alex, et al. “KFF Health Tracking Poll May 2024: The Public’s Use and Views of GLP-1 Drugs.” KFF, 10 May 2024. ↩︎

- Klein, Hayden. “Rising Costs Lead Insurers to Drop Weight Loss Drug Coverage, Further Increasing Patient Burden.” Am J Manag Care, vol. 30, no. 10, Sep. 2024, pp. 781-782. ↩︎

- Lo, Justin and Cynthia Cox. “Insurer Strategies to Control Costs Associated with Weight Loss Drugs.” Health System Tracker, June 2024. ↩︎

- Allen, Arthur. “Why Millions Are Trying FDA-Authorized Alternatives to Big Pharma’s Weight Loss Drugs.” KFF, 23 July 2024. ↩︎

- Allen, Arthur. “Why Millions Are Trying FDA-Authorized Alternatives to Big Pharma’s Weight Loss Drugs.” KFF, 23 July 2024. ↩︎

- Wienges, Chip, and Scott Scheiblin. “The Skinny on Emerging GLP-1 Exposures for the Healthcare Industry,” CRC Group, 2024. ↩︎

- Constantino, Annika Kim, and Ashley Capoot. “FDA Says the Zepbound Shortage Is over. Here’s What That Means for Compounding Pharmacies, Patients Who Used off-Brand Versions.” CNBC, 24 Dec. 2024. ↩︎

- Dunleavy, Kevin. “Novo Nordisk Asks FDA to Prevent Compounders from Making Copycat Versions of GLP-1 Star Semaglutide.” Fierce Pharma, 23 Oct. 2024. ↩︎

- Tirrell, Meg, and Tami Luhby. “‘Greed, Greed, Greed’: Sanders Demands Ozempic Maker Lower Prices.” CNN, 24 Sept. 2024. ↩︎

- Dunleavy, Kevin. “In Fight against Knockoff Weight Loss Meds, Eli Lilly Accuses Sellers of ‘deceptive’ Advertising.” Fierce Pharma, 20 June 2024. ↩︎

- “FDA’s Concerns with Unapproved GLP-1 Drugs Used for Weight Loss.” U.S. Food and Drug Administration, 18 Dec. 2024. ↩︎

- Krištopaitytė, Eglė. “Investigation: Availability of GLP-1 Drugs on the Dark Web.” Healthnews, 06 Jan. 2025. ↩︎

- Allen, Arthur. “Why Millions Are Trying FDA-Authorized Alternatives to Big Pharma’s Weight Loss Drugs.” KFF, 23 July 2024. ↩︎

- Ozdemir, Alper. “Compounding Pharmacies vs. Big Pharma: The Battle for Dominance in the Growing GLP-1 Market.” Precision Compounding Pharmacy, 22 Oct. 2024. ↩︎

- Constantino, Annika Kim, and Ashley Capoot. “FDA Says the Zepbound Shortage Is over. Here’s What That Means for Compounding Pharmacies, Patients Who Used off-Brand Versions.” CNBC, 24 Dec. 2024. ↩︎

Leave a Reply