How Tobacco Giants Hacked Hunger and Broke Our Bodies

This is the first of our three-part series on The Ozempic Era. This series explores how the Food Industrial Complex engineered an addiction crisis, how Ozempic emerged as its apparent antidote, and why millions of desperate patients betting their health on GLP-1 drugs may be making a deal with the devil.

Read The Ozempic Era, Part 0: Preview

The Great Transformation: Obesity Consumes the World

The statistics tell one story. The old photos tell another. Look through family albums from the 1950s or early ’60s, and you’ll see a different America. Beach photos, graduation ceremonies, family picnics – the people look almost impossibly lean by today’s standards. This wasn’t just aesthetics; it was the norm. In 1960, just 13% of American adults were classified as obese 1. Today, that figure seems unfathomable.

The Old Regime: When Malnutrition Was Public Enemy #1

Prior to the 1970s, malnutrition and undernourishment remained more pressing issues in many parts of the world: my maternal grandmother, who grew up in an orphanage under extreme poverty, developed rickets from malnutrition – a condition virtually unknown in America today 2. Her generation’s healthcare providers were far more preoccupied with battling diseases of deprivation – rickets, pellagra, and other nutritional deficiencies that now appear primarily in medical textbooks – rather than counting calories.

It wasn’t just about food availability. Daily life itself demanded more movement. Agricultural and factory labor dominated the workforce. Most households had a single car, if any. Suburban sprawl hadn’t yet reshaped our cities into unwalkable expanses. And perhaps most crucially, processed foods were the exception rather than the rule – most meals were cooked at home using fresh or minimally processed ingredients.

It wasn’t a golden age by any stretch of the imagination – food inequality and undernourishment remained a grim reality in parts of the U.S. and abroad. But on the whole, widespread overconsumption of calories wasn’t yet embedded into every corner of daily life.

Brave New World: Post-1970s

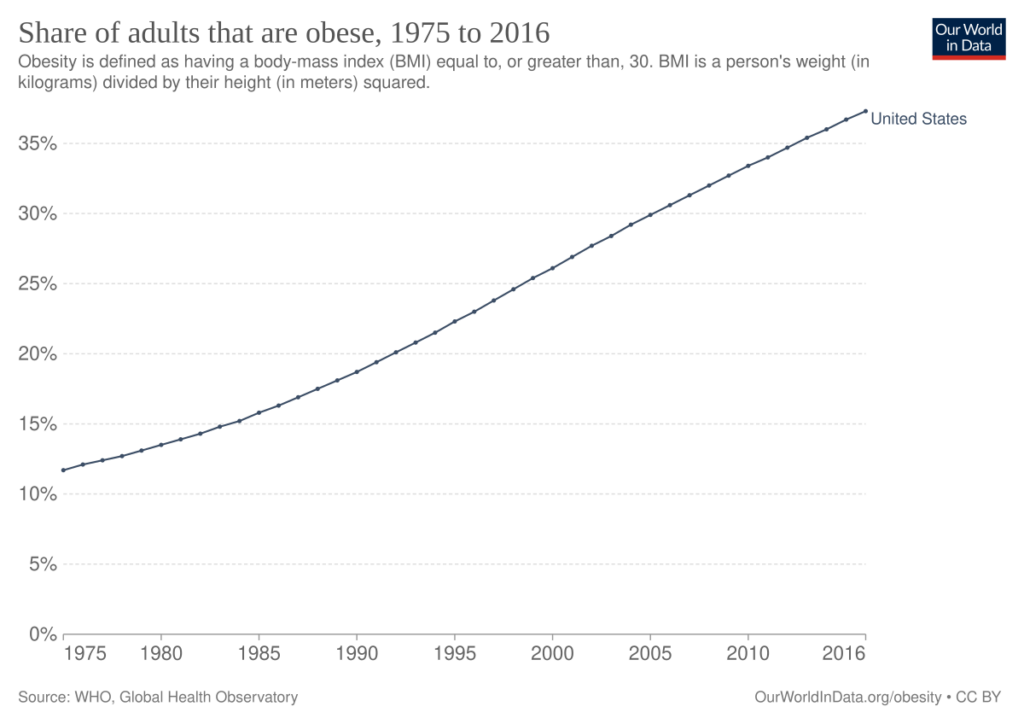

The transformation began quietly in the mid-1970s. At first, the uptick in obesity rates seemed like a statistical blip. But by the early 1980s, the trend was unmistakable: across every race, age, and gender, Americans were packing on the pounds – and fast 3. Obesity rates jumped from 13% obesity in 1960 to over 40% today 4. The U.S. now has some of the highest obesity rates in the world – over three-quarters of adults are overweight or obese 5.

Figure: Share of adults that are obese, 1975 to 2016 6

While America led this transformation, it didn’t remain an American phenomenon for long. The obesity epidemic has gone fully global, spreading first to other affluent Western nations, then to emerging economies such as China or Saudi Arabia, and now to developing nations across the global south.

Today’s numbers paint a startling picture of this global transformation: 43% of adults worldwide – over 2.5 billion people – are now considered overweight. 16% of the global adult population is classified as obese 7. Nations that once battled undernourishment now face an onslaught of fast-food chains, sugar-sweetened beverages, and shelf-stable snacks high in fat and salt.

Craveware: How the Food Industrial Complex Hacked Hunger

The conventional narrative blames the obesity epidemic on a simple calories-in, calories-out equation gone wrong. But that explanation misses the orchestrated campaign that reshaped global eating habits.

The true inflection point came in the 1980s, when major tobacco companies, facing declining cigarette sales and mounting public health concerns, began acquiring food manufacturers en masse: Philip Morris purchased General Foods in 1985 and Kraft in 1988, while R.J. Reynolds acquired Nabisco in 1985 8. These weren’t just diversification plays. The tobacco giants brought something far more valuable than capital to their new food subsidiaries: decades of expertise in creating dependency by engineering and marketing addictive products.

The results were transformative. Under tobacco company ownership, food products became dramatically more “hyperpalatable” – industry speak for engineered combinations of fats, sugars, and sodium not found in nature that trigger compulsive consumption 9. Recent research reveals the scope of this transformation: Foods owned by tobacco companies were 80% more likely to contain potent combinations of carbs and sodium and were 29% more likely to contain powerful combinations of fats and sodium 10. Today, a staggering 68% of the American food supply meets the scientific criteria for hyperpalatability 11.

This isn’t just processed food; it’s addiction engineering. The same companies that spent decades optimizing nicotine delivery systems turned their expertise to engineering foods that override natural satiety signals and hijack reward pathways in the brain. These addictive combos serve as “craveware” that hacks our brain’s reward center, enticing us to eat beyond satiety – exactly what corporate bottom lines demand. Add an onslaught of marketing campaigns and “value meals” that stack cheap calories high, and you have a perfect recipe for widespread obesity 12.

The Health Reckoning for Obesity

The consequences of this transformation extend far beyond aesthetics or clothing sizes. The medical community now finds itself battling a cascade of obesity-related health conditions that threaten to overwhelm healthcare systems globally:

| Cardiovascular Diseases | • Each 5-point increase in BMI corresponds to a 27% higher risk of coronary heart disease and an 18% increased risk of stroke 13. • Hypertension rates jump from 24% in normal-weight individuals to 54% in those with BMI ≥35 14. |

| Metabolic Disorders | • Up to 70% of patients with obesity develop dyslipidemia 15. • Type 2 diabetes risk increases dramatically with BMI 16. • Non-alcoholic fatty liver disease (NAFLD) has become endemic in obese populations 17. |

| Cancer | • Obesity is now recognized as a major risk factor for multiple cancers, including esophageal, colon, liver, pancreatic, and kidney malignancies 18. • The inflammation associated with obesity creates an internal environment that promotes tumor growth and progression |

| Other Risks | • Osteoarthritis risk increases with obesity, particularly affecting weight-bearing joints 19. • Obesity can impact fertility and increase complications during pregnancy 20. • Obesity is linked to increased all-cause mortality, with the risk increasing as BMI rises 21. |

What we’re witnessing isn’t just a public health crisis – it’s the largest transformation of human bodies in recorded history. And unlike infectious diseases or natural disasters, this epidemic was intentionally engineered, marketed, and sold to us by companies that are seeking to maximize profits at our health – and financial – expense.

Why Traditional Weight Loss Methods Are No Match for “Craveware”

The weight loss industry has thrown everything imaginable at the obesity epidemic: low-fat diets, low-carb diets, point-counting systems, meal replacements, appetite suppressants, and countless “lifestyle programs.” Americans spend over $90 billion annually on weight loss products and services 22. Yet obesity rates continue their relentless climb.

This isn’t a story of lack of willpower or dedication. These approaches rarely consider the psychological and cultural underpinnings that drive our modern eating habits.

The False Promise of Fad Diets

Every few years, a new diet promises to crack the code of sustainable weight loss. Atkins. South Beach. Keto. Paleo. Mediterranean. Each arrives with evangelical fervor and compelling before-and-after photos. Each works brilliantly – for a while 23.

The pattern is remarkably consistent:

- Phase 1: Initial rapid weight loss (primarily water)

- Phase 2: Slower but continued losses over 3-6 months

- Phase 3: Plateau

- Phase 4: Gradual regain

- Phase 5: Return to baseline weight or higher

The medical literature confirms what millions have experienced firsthand: while any calorie-restricted diet works in the short term, over half the lost weight returns within just two years. 80% of lost weight is regained within five years 24.

But here’s what the glossy diet book covers don’t tell you: each failed attempt leaves people worse off metabolically than if they’d never dieted at all. More on this soon.

Structured Weight Loss Programs: Better, But Not Enough

Commercial weight loss programs like Weight Watchers and Jenny Craig represent a more sophisticated approach. They offer structure, accountability, and some form of behavioral support. Many incorporate evidence-based strategies like regular weigh-ins, food logging, and group support 25.

The results are marginally better than self-directed dieting, but still discouraging: participants enjoy higher initial success rates and slightly better maintenance at one year. However, most participants drop out due to the cost and time commitment and go on to regain significant weight within two years 26. These programs deserve credit for recognizing that sustainable weight loss requires more than just a meal plan. Long-term success hinges on continuous support and behavioral change 27. But they’re still fighting an uphill battle against foods explicitly engineered to override their behavioral strategies.

The Devastating Impact of Weight Cycling

This is where the story takes an unfortunate turn. Each failed weight loss attempt isn’t just a return to square one – it actively damages metabolic health through a process called weight cycling or “yo-yo dieting.”

The cycle is devastating:

- Calorie restriction triggers rapid weight loss, and the body loses both fat and lean mass when on restrictive diets 28.

- Metabolic rate drops as muscle is lost, slowing or reversing weight loss progress 29.

- Intense hunger post-diet can trigger binge eating and weight regain 30.

- When weight is regained, it comes back primarily as fat since fat is regained more easily than muscle 31.

- Dieters are left worse off metabolically than if they had never tried to lose weight at all 32.

Each weight cycle leaves individuals with a laundry list of ailments:

| Body Composition Changes | • Lower muscle mass 33 • Higher body fat percentage 34 • Lower bone mineral density 35 • Increased sarcopenia and frailty 36, 37 |

| Metabolic Disruption | • Reduced metabolic rate 38 • Increased type 2 diabetes risk 39 • Greater insulin resistance 40 |

| Systemic Health Impact | • Heightened cardiovascular risk 41 • Increased inflammation markers 42 |

Studies indicate that the negative impacts of weight cycling (e.g., risk of diabetes, hypertension) may be stronger in women, older adults, and individuals with normal BMI who repeatedly attempt aggressive weight loss 43.

This metabolic damage is compounded by psychological trauma. Each failed attempt reinforces feelings of helplessness and a sense of futility 44. The cruel irony: these negative emotions often trigger comfort eating 45, feeding right into the reward pathways that “craveware” was engineered to exploit.

Truth Is, the Game Was Rigged from the Start

Even the most promising traditional weight loss approaches share a fatal flaw: they require constant vigilance against foods literally designed to break down willpower. Maintaining this vigilance requires ongoing support – regular dietitian meetings, therapy sessions, medical supervision – that few patients or clinicians can sustain indefinitely.

Consider the many resources required for successful long-term weight management:

- Regular healthcare provider visits and supervision

- Cognitive behavioral therapy or food counseling

- Dietitian-led nutrition education and meal planning

- Fitness guidance and facilities

- Food preparation equipment and time

- Social support systems

Now consider that these resources must be maintained indefinitely while navigating a busy life saturated with hyper-convenient, heavily subsidized, hyperpalatable junk foods specifically engineered to trigger overconsumption.

Traditional weight loss methods are simply no match for craveware. These tools place the entire burden of behavior change on individuals while ignoring the sophisticated Big Tobacco addiction playbook that created the problem in the first place.

If we were to have any hope for success in the war on obesity, we needed a new class of tools powerful enough to counter industrially engineered food cravings.

Enter Ozempic.

Citations

- May, Ashleigh L. “Obesity – United States, 1999–2010.” Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, 22 Nov. 2023. ↩︎

- Bivins, Roberta. “Ideology and Disease Identity: The Politics of Rickets, 1929–1982.” Medical Humanities, vol. 40, no. 1, 2014, pp. 3–10. ↩︎

- Rodgers, Anthony, et al. “Prevalence Trends Tell Us What Did Not Precipitate the US Obesity Epidemic.” The Lancet Public Health, vol. 3, no. 4, 2018, pp. e162–e163. ↩︎

- Temple, Norman. “The origins of the obesity epidemic in the USA–lessons for today.” Nutrients, vol. 14, no. 20, 12 Oct. 2022, p. 4253. ↩︎

- Agrawal, Nina. “Three-Quarters of U.S. Adults Are Now Overweight or Obese.” The New York Times, 14 Nov. 2024. ↩︎

- “Share of adults that are obese, 1975 to 2016.” Our World In Data. ↩︎

- “Obesity and Overweight.” World Health Organization, Mar. 2024. ↩︎

- O’Connor, Anahad. “Many Junk Foods Today Were Made and Marketed by Big Tobacco.” The Washington Post, Sept. 2023. ↩︎

- O’Connor, Anahad. “Many Junk Foods Today Were Made and Marketed by Big Tobacco.” The Washington Post, Sept. 2023. ↩︎

- Fazzino, Tera L., Daiil Jun, Lynn Chollet‐Hinton, et al. “US tobacco companies selectively disseminated hyper‐palatable foods into the US food system: Empirical evidence and current implications.” Addiction, vol. 119, no. 1, 8 Sept. 2023, pp. 62–71. ↩︎

- Lynch, Brendan M. “Study Shows Cigarette Makers Also Made U.S. Food More ‘Hyperpalatable.’” KU News, Sept. 2023. ↩︎

- Temple, Norman. “The origins of the obesity epidemic in the USA–lessons for today.” Nutrients, vol. 14, no. 20, 12 Oct. 2022, p. 4253. ↩︎

- Bakhtiyari, Mahmood, et al. “Contribution of obesity and cardiometabolic risk factors in developing cardiovascular disease: A population-based Cohort Study.” Scientific Reports, vol. 12, no. 1, 28 Jan. 2022. ↩︎

- Volpe, Massimo, and Giovanna Gallo. “Obesity and cardiovascular disease: An executive document on pathophysiological and clinical links promoted by the Italian Society of Cardiovascular Prevention (SIPREC).” Frontiers in Cardiovascular Medicine, vol. 10, 13 Mar. 2023. ↩︎

- Pi-Sunyer, F. Xavier. “Comorbidities of overweight and obesity: Current evidence and research issues.” Med Sci Sports Exerc, vol. 31, no. Supplement 1, Nov. 1999. ↩︎

- Liu, Natalie, et al. “Obesity and BMI Cut Points for Associated Comorbidities: Electronic Health Record Study.” Journal of Medical Internet Research, Aug. 2021. ↩︎

- Pi-Sunyer, F. Xavier. “Comorbidities of overweight and obesity: Current evidence and research issues.” Med Sci Sports Exerc, vol. 31, no. Supplement 1, Nov. 1999. ↩︎

- Lim, Yizhe, and Joshua Boster. “Obesity and Comorbid Conditions.” StatPearls, 27 June 2024. ↩︎

- Liu, Natalie, et al. “Obesity and BMI Cut Points for Associated Comorbidities: Electronic Health Record Study.” Journal of Medical Internet Research, Aug. 2021. ↩︎

- Gautam, Divya, et al. “The challenges of obesity for fertility: A FIGO literature review.” International Journal of Gynecology & Obstetrics, vol. 160, no. S1, Jan. 2023, pp. 50–55. ↩︎

- Volpe, Massimo, and Giovanna Gallo. “Obesity and cardiovascular disease: An executive document on pathophysiological and clinical links promoted by the Italian Society of Cardiovascular Prevention (SIPREC).” Frontiers in Cardiovascular Medicine, vol. 10, 13 Mar. 2023. ↩︎

- LaRosa, John. “U.S. Weight Loss Industry Grows to $90 Billion, Fueled by Obesity Drugs Demand.” Market Research, 6 Mar. 2024. ↩︎

- Tahreem, Aaiza, et al. “FAD diets: facts and fiction.” Frontiers in Nutrition, vol. 9, 5 July 2022. ↩︎

- Hall, Kevin D., and Scott Kahan. “Maintenance of lost weight and long-term management of obesity.” Medical Clinics of North America, vol. 102, no. 1, Jan. 2018, pp. 183–197. ↩︎

- Laudenslager, Marci, et al. “Commercial weight loss programs in the management of obesity: An Update.” Current Obesity Reports, vol. 10, no. 2, 20 Feb. 2021, pp. 90–99. ↩︎

- Atallah, Renée, et al. “Long-term effects of 4 popular diets on weight loss and cardiovascular risk factors.” Circulation: Cardiovascular Quality and Outcomes, vol. 7, no. 6, Nov. 2014, pp. 815–827. ↩︎

- Laudenslager, Marci, et al. “Commercial weight loss programs in the management of obesity: An Update.” Current Obesity Reports, vol. 10, no. 2, 20 Feb. 2021, pp. 90–99. ↩︎

- Yates, T., et al. “Impact of weight loss and weight gain trajectories on body composition in a population at high risk of type 2 diabetes: A prospective cohort analysis.” Diabetes, Obesity and Metabolism, vol. 26, no. 3, 14 Dec. 2023, pp. 1008–1015. ↩︎

- Hall, Kevin D., and Scott Kahan. “Maintenance of lost weight and long-term management of obesity.” Medical Clinics of North America, vol. 102, no. 1, Jan. 2018, pp. 183–197. ↩︎

- Field, A E, et al. “Association of weight change, weight control practices, and weight cycling among women in the nurses’ health study II.” International Journal of Obesity, vol. 28, no. 9, 20 July 2004, pp. 1134–1142. ↩︎

- Yates, T., et al. “Impact of weight loss and weight gain trajectories on body composition in a population at high risk of type 2 diabetes: A prospective cohort analysis.” Diabetes, Obesity and Metabolism, vol. 26, no. 3, 14 Dec. 2023, pp. 1008–1015. ↩︎

- Schofield, S E, et al. “Metabolic dysfunction following weight cycling in male mice.” International Journal of Obesity, vol. 41, no. 3, 14 Nov. 2016, pp. 402–411. ↩︎

- Yates, T., et al. “Impact of weight loss and weight gain trajectories on body composition in a population at high risk of type 2 diabetes: A prospective cohort analysis.” Diabetes, Obesity and Metabolism, vol. 26, no. 3, 14 Dec. 2023, pp. 1008–1015. ↩︎

- Tannir, Hana, et al. “Lifetime weight cycling and central fat distribution in females with obesity: A brief report.” Diseases, vol. 8, no. 2, 26 Mar. 2020, p. 8. ↩︎

- Fogelholm, M., et al. “Association between weight cycling history and bone mineral density in premenopausal women.” Osteoporosis International, vol. 7, no. 4, July 1997, pp. 354–358. ↩︎

- Rossi, Andrea P., et al. “Weight cycling as a risk factor for low muscle mass and strength in a population of males and females with obesity.” Obesity, vol. 27, no. 7, 23 June 2019, pp. 1068–1075. ↩︎

- Yates, T., et al. “Impact of weight loss and weight gain trajectories on body composition in a population at high risk of type 2 diabetes: A prospective cohort analysis.” Diabetes, Obesity and Metabolism, vol. 26, no. 3, 14 Dec. 2023, pp. 1008–1015. ↩︎

- Prado, Carla M, et al. “Muscle matters: The effects of medically induced weight loss on skeletal muscle.” The Lancet Diabetes & Endocrinology, vol. 12, no. 11, Nov. 2024, pp. 785–787. ↩︎

- Schofield, S E, et al. “Metabolic dysfunction following weight cycling in male mice.” International Journal of Obesity, vol. 41, no. 3, 14 Nov. 2016, pp. 402–411. ↩︎

- Li, Xin, et al. “Impact of weight cycling on CTRP3 expression, adipose tissue inflammation and insulin sensitivity in C57BL/6J MICE.” Experimental and Therapeutic Medicine, Sep. 2018. ↩︎

- Anderson, Emily K., et al. “Weight cycling increases T-cell accumulation in adipose tissue and impairs systemic glucose tolerance.” Diabetes, vol. 62, no. 9, 15 Aug. 2013, pp. 3180–3188. ↩︎

- Anderson, Emily K., et al. “Weight cycling increases T-cell accumulation in adipose tissue and impairs systemic glucose tolerance.” Diabetes, vol. 62, no. 9, 15 Aug. 2013, pp. 3180–3188. ↩︎

- Kim, Su Hwan, et al. “The association between diabetes and hypertension with the number and extent of weight cycles determined from 6 million participants.” Scientific Reports, vol. 12, no. 1, 28 Mar. 2022. ↩︎

- Hall, Kevin D., and Scott Kahan. “Maintenance of lost weight and long-term management of obesity.” Medical Clinics of North America, vol. 102, no. 1, Jan. 2018, pp. 183–197. ↩︎

- Field, A E, et al. “Association of weight change, weight control practices, and weight cycling among women in the nurses’ health study II.” International Journal of Obesity, vol. 28, no. 9, 20 July 2004, pp. 1134–1142. ↩︎

Leave a Reply